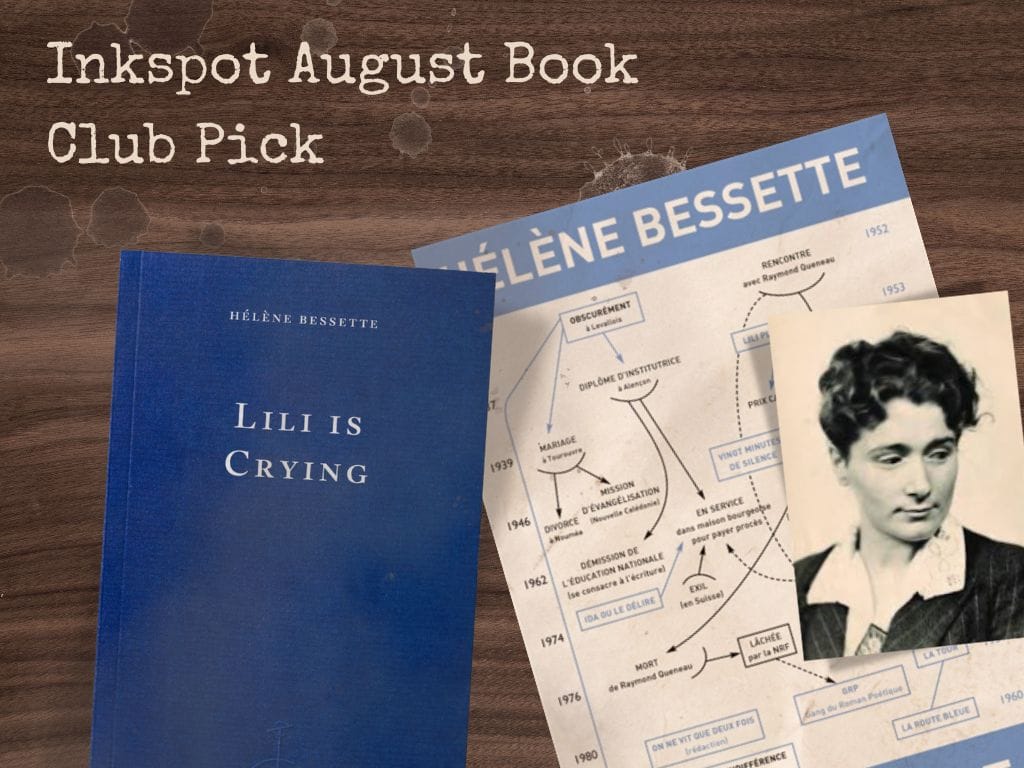

August’s Indie Book is Lili is Crying by Hélène Bessette, (1918 – 2000) translated from the original French by Kate Briggs, and published by Fitzcarraldo Editions in their signature International Yves Klein ultramarine blue with white lettering. Their non-fiction books are white with IYK blue lettering, always with the same special custom serif font, called Fitzcarraldo. Publishing houses spend vast fortunes on book covers, so their decision to make their books distinct but uniform is a smart one, as their books convey a message, a way to ‘signal your cleverness’ (according to theface.com) even though they all look the same. Fitzcarraldo are known for their experimental fiction, for rediscovering books which deserve a new generation of readers, for publishing Nobel laureates, for books which push boundaries and bold ideas, for ‘never publishing a book for commercial reasons’ (although I’d be surprised if they were totally averse to commercial success) and dedicating themselves to creating future classics. According to founder Jacques Testard, the name comes from the 1982 Werner Herzog movie of the same name, and is a ‘not-very-subtle metaphor on the stupidity of setting up a publishing house, which is like dragging a 320-ton steamboat over a muddy mountain in the Amazon jungle.’ As the co-founder of an indie publishing house, I know how he feels.

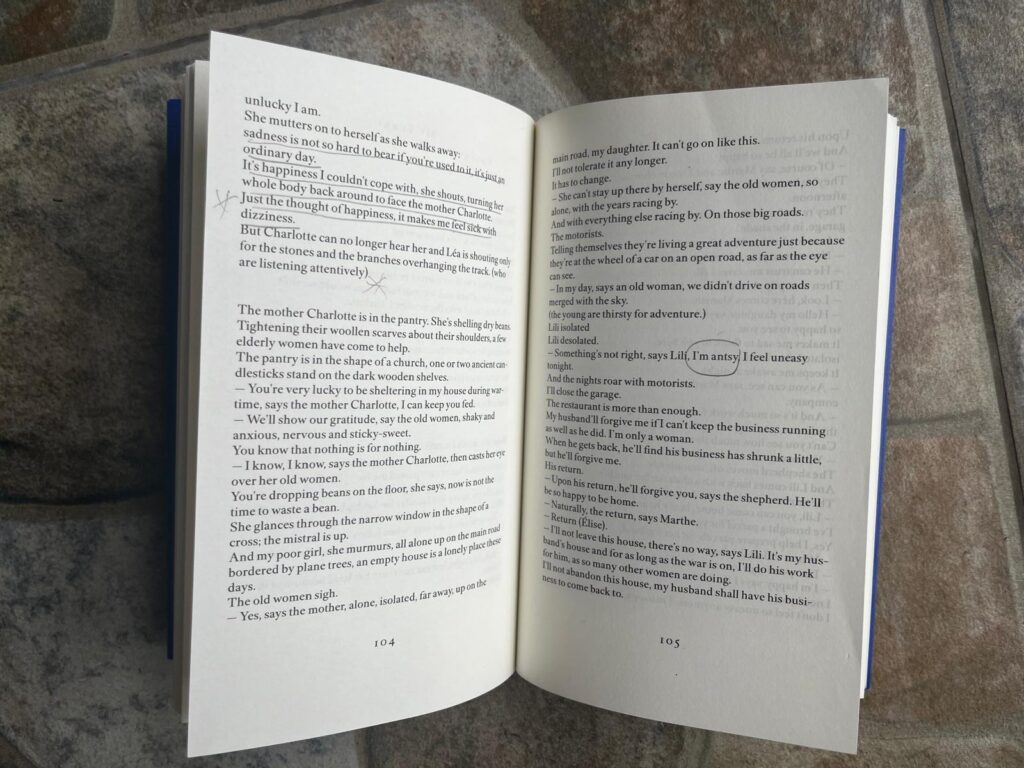

The feel and the look of Lily Is Crying, like all FE’s other books, is wonderful. This one is slim, it’s quality, the weave of the cover is visible to the naked eye and discernible by touch beneath the fingerpads and has front and back flaps. There is nothing on the cover other than the author’s name and the title and the Fitzcarraldo watermark. The paper is a beautiful expensive cream, and the pages invite you in with plenty of white space, each a different shape and layout. The publisher and the translator have colluded in obeying Bessette’s wish to honour a book as a thing in itself, and not just a series of words conveying a story which can be typed on any old scrap.

Lily Is Crying is a stripped down narrative, more of a poem than a novel. Lili’s mother, Charlotte, is loving towards her daughter, but tyrannically bends her to her will, guilting her into living a life with Charlotte at its centre, an inversion of the usual expectation: that parents should help their children to live the best possible version of their lives, rather than use them as instruments for their own ease or vanity. Lili’s mother prevents her from having the man she loves; so out of spite she marries someone that her mother comes to hate, not able to bear competition for Lili’s attention. The husband loves Lili, but is treated shabbily by both women; by Charlotte with shocking hostility, by Lili with careless neglect.

I read the book a second time, purely for the pleasure of the language, while always remaining conscious that the book is a translation. I would have loved to read Briggs’s rendering of the language side by side with the original French, as I had so many questions about the possible word choices. Sadly she was not able to take part in a Q&A.

Take the following, from my favourite passage, where Lili falls in love with the shepherd, who she has known all her life. (Huge apologies – this is not exactly Bessette’s original language, this is a translation of Briggs’s English back into French. I had endless trouble getting a copy of Lili Pleure, the original.) The bold type is my own:

Lili a rencontré le berger

Chez Élise

Et ils se sont vus.

Ce n’est pas la première fois que leurs chemins se croisent.

On s’est croisés plusieurs fois auparavant

Mais on ne s’était jamais vus.

Maintenant, nous sommes ici ensembles, et parce qu’on est seuls dans la même pièce,

on ne peut s’empêcher pas de se regarder dans les yeux.

Nos regards se croisent.

Nos chemins se croisaient tout le temps.

Mais aujourd’hui, l’air entre nous se déchire

et un amour rouge vif se répand comme une flaque de sang d’une

blessure impossible à refermer, impossible à refermer, et

que personne ne pourrait jamais réparer (comme un cauchemar).

Here is Briggs’s translation:

Lili ran into the shepherd.

At Elise’s place

And they saw each other.

It isn’t the first time their paths have crossed.

We’ve run into each other countless times before

But we’ve never seen each other.

Now here we are, and because we’re alone in the same room,

we can’t stop gazing into each other’s eyes.

Gazes knitting together.

Our paths would cross all the time.

But today the air between us is being ripped apart

and bright red love is spreading like blood pooling from a

wound that it’s impossible to close, impossible to close, and

that no one could ever repair (like a nightmare).

Let’s take the subtlety first: ‘We’ve run into each other countless times before

But we’ve never seen each other.’ So clever, so economical. Briggs could just as easily have written: ‘We’ve crossed paths many times before, but we’ve never met.’ Instead, they truly ‘see’ each other for the first time.

Then there’s the beauty of the language, the gentle sound belying the meaning (Go on, say it aloud in your best Inspector Clouseau accent: no one’s listening!): ‘l’air entre nous se déchire’, ‘the air between us is being ripped apart, and bright red love is spreading like blood pooling from a wound that’s impossible to close…’ So beautiful. So violent! The author and the translator both use words to paint a picture of a passion so desperately physical that Lili cannot resist it, and how could we judge her for not even trying?

Think about the individual word choices. (Again, apologies to Bessette and Briggs for failing to lay my hands on the original text.) ‘Un amour rouge vif’ is translated as ‘bright red love’. Briggs could have described this love as living or vibrant, but the simplicity of ‘bright red’ works best as it’s part of a bigger mental image. Then there’s ‘comme une flaque de sang d’une blessure impossible à refermer, impossible a refermer…’ ‘Une flaque’ can be translated literally as ‘a puddle’. Can you imagine how easily, how awfully, how bathetically this image could have been ruined by ‘a puddle of blood’? Similarly, ‘la blessure’ can be translated as ‘injury’ as well as ‘wound’. Joggers and DIY enthusiasts get injured. On the other hand, saints, medieval warriors, Knights Templar, soldiers fighting to the death and of course poetic lovers sustain wounds. Then there’s the poetry of the repetition: ‘impossible à refermer, impossible à refermer…’ The wound cannot be closed. It’s not Lili’s fault, and her husband, poor man, must therefore suffer. Of course, this being a French novel, he is not the only one who will suffer. Suffering is part of la condition humaine, mon ami.

Kate Briggs is a novelist and the author of This Little Art, a treatise on translation which is part memoir, part essay and part literary criticism. She translated the lecture notes of literary theorist and philosopher Roland Barthes, and wrote an absorbing article in the Yale Review on Hélène Bessette and the act of translating her novel: https://yalereview.org/article/kate-briggs-bessette-french-fiction. She’s based in Rotterdam, where she teaches at the Piet Zwart Institute. She’s also the co-founder of Short Pieces That Move:

https://www.instagram.com/shortpiecesthatmove.

The process of translation can be controversial. According to Briggs, it’s not always about finding the equivalent word. It’s about conveying the pace, the tone and as much what is unsaid as what is laid out on the page. Translating Bessette could not have been easy, as the novel is full of pauses, fractured language, unexpected repetitions and leaps back and forth in time.

Briggs argues that the translator is very much a part of the creative process, and I hope the example above illustrates how a translation can be faithful to the spirit and mood of the original while possibly straying from exact equivalence. Other translators have taken a very different view. Vladimir Nabokov’s translation of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin was apparently so doggedly literal that the end result was turgid and practically unreadable, and even his most ardent fans hated it. He declared that ‘the clumsiest literal translation is a thousand times more useful than the prettiest paraphrase.’ This is such a surprise, as Nabokov’s own prose is so playful and sparkling. Then, on the other end of the spectrum, Deborah Smith courted controversy with her translation of Han Kang’s The Vegetarian. She was accused of embellishing the original, of ‘over-translating’, of adding phrases and imagery not present in the original Korean. Apparently these nuggets are known by translators as ‘Easter eggs’ and are occasionally smuggled in to the receiving language when the translator is particularly enamoured of a phrase or piece of imagery. I can understand this urge: it must be sorely tempting to sneak a bon mot or two in.

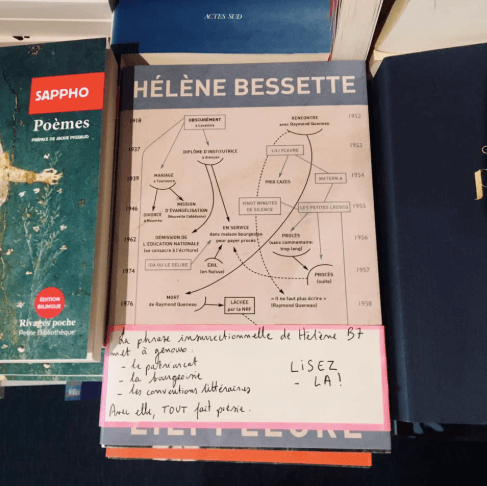

Bessette herself had a highly chequered writing career. She was the author of thirteen novels and was initially discovered by Raymond Queneau of Gallimand, who recognised the originality of her writing. As well as Queneau, she was praised by several other literary heavyweights, including Marguerite Duras and Nathalie Sarraute, and she won the Prix Goncourt for Lily Pleure, but despite this, her books stubbornly refused to sell, and were largely out of print by the time of her death in 2000. More recently, a few indie French publishers have recognised and republished her works. A new French edition has been published by Le Nouvel Attila in 2020, but all I could find was a Facebook page, not even a website. Apparently they focus on avant-garde and neglected literature, much like Fitzcarraldo in fact. The picture of the book with that very alluring and very typically French scribble describing her as Hélène B7 (geddit!) with the command ‘Lisez-la!’ (Read her!) makes me really, really, want to get hold of the text in the original. It has become an idée fixé.

Bessette’s initial promise was never fulfilled. It appears that from the 1960s onwards, her career took one dark turn after another. She and Gallimand, her publisher, were sued for defamation in the 1960s by one of her childhood friends, who asserted that Bessette’s novel, Les Petits Lecocq was a damaging account of her own family. The plaintiff won the court case, winning substantial damages, and the book had to be severely altered or withdrawn. This caused major damage to Bessette’s reputation.

In 1973, she took her publisher, Gallimand, to court. Gallimand, by this point, had refused to publish her new work, and yet also contractually prevented her from finding new publishing opportunities. In 1976, they finally cut her loose, and without their prestige and backing, she was effectively blacklisted by the French publishing world. Then, in 1978, one of her sons, Jean, died. Naturally, this was devastating, and from this point on, her writing career petered out, and she eked a living in other spheres to support herself. By all accounts, she sank into obscurity for the last thirty years of her life, and if she wrote anything during this period, there is no evident sign of it.

Her younger son, Gilles Bessette, survived her, and has played an active part in keeping her legacy alive. She had a unique talent, and really deserves a new readership. Bravo, Fitzcarraldo, for rediscovering her and to Kate Briggs for doing such justice to her poetic style.